During its brief 11 days of public-albeit-limited existence, Google+ has breathed new life into online discourse. It also has brought new interest and attention to Google's Picasa service, which allows users to share photos to Google+.

Both Google+ and Picasa are governed by Google's Terms of Service, and involve a nonexclusive license of user data to Google. Take away the license, and you take the "share" out of a sharing service. Users are right to pay attention to the scope and implications of the license, and it's fantastic to see people examining it and making sure they're comfortable with the terms.

Professional photographer, podcaster, and prolific blogger Scott Bourne is no stranger to giving close reads to user license grants. Scott has decided not to use Google services in connection with his photography because he's rightly concerned it's impossible for him to grant an exclusive license for use and display of his work — something he and other photographers routinely need to do — if he has already licensed those rights elsewhere. It's an excellent point that photographers should bear in mind when using any Web service that stores, displays, and distributes their work. (We discussed this more on TWiL last week in connection with looking at the Dropbox terms of service.)

For users who don't need, as a matter of livelihood, to grant exclusive licenses to the text or photos they might otherwise share on a social network, Google's terms are a different matter. They grant Google the license to use submissions as necessary to run its services, with the following limitation:

This license is for the sole purpose of enabling Google to display, distribute and promote the Services...

"The Services" are elsewhere defined as Google's products, software, services and web sites. Google would have a hard time using user content for anything other than operating and "promoting" its services (more on that below) given this language.

There are, however, a couple of areas where, as a lawyer and user, I wish the Google terms were more clear and user-cognizant.

First, users agree to let Google "make [their] Content available to other companies, organizations or individuals with whom Google has relationships for the provision of syndicated services," and that Google and those third parties may "use such Content in connection with the provision of those services." "Syndicated services" aren't otherwise defined, so I'm not sure what to make of this. What kind of activity is this intended to cover? API calls? RSS and Atom? It would be nice to see an explanation there, bearing in mind that while users may decide they trust Google, granting unspecified, Google-discretionary rights to "other companies, organizations or individuals with whom Google has relationships" is (or should be) a user red flag. Those relationships are Google's, not the user's.

Second, and another user red flag issue, is the "promotion" license. By signing up for Picasa and Google+, users do not reasonably contemplate pictures of their little "Sophie," conscientiously shared only to a "family" circle, showing up in ads or other materials Google may use to "promote" its services. I'm not saying Google would do this, but if that's not the intent, the license is too broad and the language should change. Worse, it's off-putting and inconsistent with the huge strides Google is making on the user trust, confidence, and privacy fronts with its Circles system. My suggestions: either eliminate "to promote" from the description of the license purpose, or provide reasonable limits, choices, and opt-outs for users for what kind of promotion is acceptable, and which submissions, if any, are eligible. (Maybe some parallel to Circles could be useful in implementing.) Surprises on this front are frustrating for users, and a potential PR disaster for the service — as Google well knows.

Bottom line: I'm not personally overwrought by the license Google asks users to grant, but it could use some clarification and adjustment on the issues of third parties and promotional use.

Also worth noting:

- The "Ending your relationship with Google" section, paragraph 13 of the terms, is a well-written, straightforward, user-friendly complement to Google's Data Liberation Front.

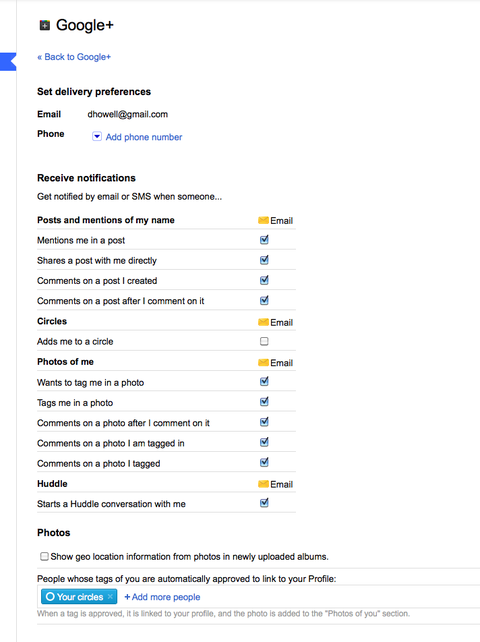

- Picasa supports Creative Commons. Go to Picasa's Settings > Privacy and Permissions tab, and you'll see four CC licenses available. Unfortunately, this is a batch selection, not a photo-by-photo one. (Another potentially good place to implement Circles-type controls.)

Updates, July 11, 2011:

- William Carleton comments he thinks the full/downloaded app version of Picasa allows for photo-by-photo license selection. I've been using Picasa Web Albums, which is all of the product a user might ever see if they're using it solely in connection with Google+.

- Trout Monfalco points out that Twitpic recently used its licenses from users to enter into a deal with World Entertainment News Network whereby the latter will sell images originally posted on Twitpic for publication. (See Joshua Brustein/NY Times, Fine Print Blurs Who's in Control of Online Photos.) Remember that Google's terms of service expressly limit the purpose of the license to "enabling Google to display, distribute and promote the Services" (presumably ruling out deals like the Twitpic/WENN one as long as the limitation remains in place). Note Facebook has no such "purpose" limitation; users simply grant Facebook a license to "use" their "IP content."

- Rolando Gomez further examines Google's terms of service from a photographer's perspective, and particularly focuses on the perpetual, nonrevocable nature of the user license. (The content license to Google would survive even a user's express termination of her/his relationship with Google per paragraph 13 of the terms, since rights "which are expressed to continue indefinitely" are exempted.) The duration of the user license on Facebook has been subject to much public discussion and backlash, and it currently "ends when you delete your IP content or your account unless your content has been shared with others, and they have not deleted it." So, is Google guilty of a "rights grab" if the user license remains nonrevocable? I think the express "purpose" limitations go a long way toward making the duration of the license (i.e., as long as the original copyright exists) palatable. Creative Commons licenses too are nonrevocable. And as Creative Commons wisely cautions, "if you depend on controlling the copyrights in your resources for your livelihood, you should think carefully before giving away commercial rights to your creative work."

Update, July 12, 2011:

See also photographer Jim Goldstein, How I Evaluate Terms of Service for Social Media Web Sites – Google+

Saturday, July 16, 2011 at 3:37AM

Saturday, July 16, 2011 at 3:37AM