Ceballos Whiffs On The Web

Thursday, June 8, 2006 at 6:34PM

Thursday, June 8, 2006 at 6:34PM It's encouraging and impressive that a number of recent U.S. judicial decisions have accounted for the realities and impact of modern online communications tools in arriving at their results. I'm thinking specifically of:

- Apple v. Does, where the California Court of Appeal waded into the age-old "Is blogging journalism?" debate and wisely decided in appropriate circumstances Web-native material is "conceptually indistinguishable" from other news publication means;

- DiMeo v. Max (see Law.com and Evan Brown), which followed in the 9th Circuit's footsteps (see Batzel v. Smith, as summarized in PC Magazine: Free-Er Speech on the Net) and found that Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act will immunize a message board host from the libelous activities of third party contributors; and

- Traffic-Power v. Wall (well summarized by Eric Goldman), where a federal district court found that accepting comments on a blog does not, in and of itself, trigger personal jurisdiction over the blogger in a commenter's locale (which has remained an open question).

The U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Garcetti v. Ceballos (PDF) is another story. (For coverage, see particularly Marty Lederman and Jack Balkin, and generally Memeorandum, Memeorandum, and Technorati.) Ceballos missed the boat by missing the Web, and the way its tools give rise to complicated gray areas when it comes to deciding things like whether or not a particular activity is among one's professional pursuits.

To recap what was at stake and what the Court held, here's how Marty Lederman summed things up:

Today the Court held that most, if not quite all, of the speech made in a public employee's official capacity is entitled to no constitutional protection at all. The case involved a deputy district attorney, Ceballos, who worked in the Los Angeles County District Attorney's Office. Ceballos discovered what he considered to be serious misrepresenations in an affidavit that his office had used to obtain a search warrant – and he did what an employee was supposed to do in such a situation: Not announce it to the public, but instead bring the alleged wrongdoing to the attention of his supervisors. Those supervisors disagreed with Ceballos's concerns; and Cebellos claimed that he was thereafter subjected to a series of retaliatory employment actions. [...]

The looming question in the case was not so much the outcome but the Court's rationale — and, in particular, the question whether the Court would hold that a government employee's speech in her "official capacity" is entitled to no constitutional protection — not even of the modest Pickering/Connick variety. The Solicitor General urged the Court to hold that "the First Amendment has nothing to say about actions based on [a] public employee's performance of his duties."

Today, the Court took that very significant step, holding that "when public employees make statements pursuant to their official duties, the employees are not speaking as citizens for First Amendment purposes, and the Constitution does not insulate their communications from employer discipline." This apparently means that employees may be disciplined for their official capacity speech, without any First Amendment scrutiny, and without regard to whether it touches on matters of "public concern" — a very significant doctrinal development.

Jack Balkin captures why the future claims of parties like Caballos are on a collision course with the tools and activities of the Live Web and our increasingly "always-on" world: "[T]he Court's decision doesn't really create a bright line rule, because the boundaries of what is within an employee's job description may turn out to be quite contestable, and will be contested in future cases."

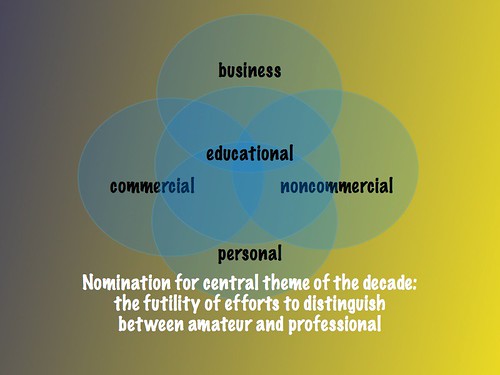

The Court found Ceballos' speech was unprotected because it was "part of what he...was employed to do." (Emphasis added.) An employee who is "simply performing his or her job duties" affords no occasion, according to the majority, for First Amendment balancing. (Emphasis added.) Though the Court found that "[e]mployees who make public statements outside the course of performing their official duties retain some possiblity of First Amendment protection because that is the kind of activity engaged in by citizens who do not work for the government," it seems to have ignored the fact it is becoming increasingly common — thanks to weblogs and other tools of the Live Web — for employees to make public statements that are within the scope of their official duties, or at least related to them in a direct or indirect manner. The Court hasn't accounted for someone who speaks publicly (as on a blog), but not entirely — or perhaps even primarily — as a non-work-related endeavor. Also strange is the Court's emphasis on the fact Ceballos physically "went to work" to perform these tasks, implying this circumstance speaks to whether the tasks were within his job duties. Presumably the parallel antiquated concept would also hold true: that activities performed outside the physical workplace somehow automatically aren't part of work.

Rory Perry is a fantastic government employee blogger. Is his a "citizen" blog, or is it part of his work? Go take a look. You tell me.

I won't even begin to attempt to list all the blogs I can think of by those employed by public universities — professors, in particular. Part of their jobs, or not? (The Court acknowledged a different analysis might be necessary in a case involving such a speaker, to account for the "additional constitutional interests" his or her status as a scholar and academic instructor could entail.)

The results of the recent BlogHer "Blogging Naked at Work" survey, which "explored personal, or 'naked' blogging on professionally-focused blogs," are also telling. E.g.:

The positive outcomes for business bloggers who share personal information on their business blogs include building online communities (42 percent), positive customer feedback (39 percent), favorable press (35 percent), and writing or speaking engagements (28 percent.)

Also: 36% of the survey respondents thought of themselves as "both personal and business bloggers."

In an apparent effort to downplay the importance of restricting the scope of the First Amendment, at the end of the majority opinion Justice Kennedy emphasizes the separate "powerful network of legislative enactments — such as whistle-blower protection laws and labor codes — available to those who seek to expose wrongdoing." Well, sure. But that doesn't mean the Court's decision isn't based on a premise — i.e., that professional and personal pursuits are readily severable — the viability of which becomes more and more shaky with each day's batch of additions to the Technorati index.

[Tags: garcetti v. ceballos, first amendment, live web, bloglaw]

Reader Comments